Why do Americans eat a lot of junk food? Because it’s the easy way out.

Unhappy? Open a candy bar. You’ll feel happy again in seconds. Kid crying? Hand them a fun-sized candy bar. They will be quiet.

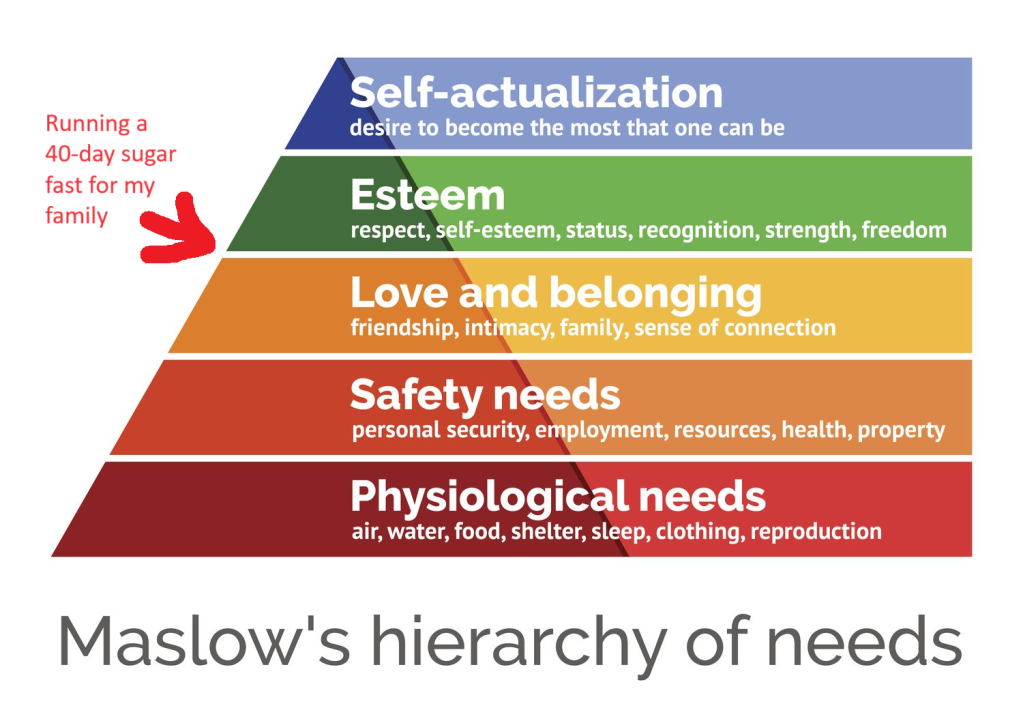

If you are struggling with paying bills or health (I know, the health one is ironic here), then you’ll tend to reach for anything that is fast and easy to deal with immediate problems.

For me, I decided to wait until my semester is over, so I won’t be attempting this while teaching or traveling. A 40-day sugar fast for the whole family technically began on May 1, but the grocery shopping changed earlier. The idea was to eat down junk and not buy new for over a week.

Forty days isn’t much in the big scheme. The idea is to make a deposit on health. Possibly, I’ll break a mild sugar addiction to the point where the body doesn’t expect it so much. Maybe something that we end up doing to meet this artifactual goal will end up getting into the routine on a regular part of the year when there is more travel and work. Part of the problem I identify is that there are points throughout the day where people feel unhappy. If sugar is on hand, then there is a tendency to reach for it. Part of what I’m going to do is insert more healthy food and activities, but of course that is a lot more work. If it’s just not there, people barely miss it.

I’m already so much happier at home. There is barely any sugary junk food left in the house. Now if the kids circulate the kitchen, I don’t have to stress out and yell at them to not eat cookies before dinner or whatnot.

Internet: So, you’re going to meal plan and not eat dessert for a month? This was worth telling everyone?

Me: I’ve been thinking about it constantly since Christmas.

Internet: Wasn’t this the site where we get more optimistic about the world?

Me: There are some things I read about and decided against. I will not worry about sugar in sauces (e.g. Chicken teriyaki bowl). I will not cut out bread or pasta. There is a sliding scale of how healthy you can be and how much time you are willing to put in. I have decided on a level of effort and a fixed amount of time. I’m not even going to turn down cookies if they are offered to us for free. The most important thing is to stop buying junk from the grocery store. It’s financially very cheap, but actually very costly.

P.S. It’s a small step toward getting my personal chef, but I saw an ad for Walmart “emeals” which is more intelligent grocery delivery plus recipes. I haven’t tried it myself, but it seemed like an update on What the Superintelligence Can Do For Us. When I have the equivalent of “former restaurateur, Frances,” in my house, then I just won’t need anything else and innovation can stop there, thanks.